Introduction

At the point of writing this, I’ve been working as a fitness coach in the industry for 16 years. Ideas and practises have evolved in that time. We’ve gone from lots of sitting on machines back to using freeweights and bodyweight exercises. We’ve seen many fads come and go, but some approaches arrive on the scene which seem strong years later. The strength and conditioning community has also seen a change in recent years with coaches coming from other disciplines like Parkour, Climbing, Dance and Capoeira. They’ve brought with them their felt knowledge of how the body moves and added that to the more classical ideas already there. Throughout all that time I’ve kept studying, watching, comparing and developing my personal interpretation of these ideas. I’ve seen where philosophies overlap and where they differ, taken what I feel is the most useful and dropped what I deem to not work as well.

Through this process I’ve developed my own movement philosophy which guides my programming. There are 3 big themes of this philosophy which I’ll run through today: The Evolutionary Argument, Biomechanics and Anatomical Discoveries. These themes then inform my decisions on what type of movements that I programme for my trainees.

Inspiration

It’s important to me to state whose shoulders I stand on. Over the years, I’ve read books, watched video lectures or attended courses from Paul Chek (Primal Patterns/The Chek Institute), Greg Glassman (CrossFit), Erwin Le Corre (MovNat) and Ido Portal. In more recent times, I’ve been following Naudi Aguilar (Functional Patterns), Tim Shieff (The School of Biomechanics) and Rafe Kelley (Evolve Move Play). So, whilst nothing here is all mine or original, the combination of their ideas may be unique. I’m a never ending student and have learned loads from all these great teachers.

Evolutionary Argument

One of the common themes in most of the big thinkers around movement has been to consider “What movements did our ancestors primarily perform?”, or, more simply “What did we evolve doing?”

The most fundamental movements that were crucial to human development were Standing, Walking, Running and Throwing. If you compare the human body to those of our primate cousins, one of the most striking differences is our upright posture and powerful glutes (bum muscles), relative to our upper body strength. We are runners. One of my teachers once said “A human that can’t run is like a fish that can’t swim or a bird that can’t fly” and this rings true to me. I think that movement training should aim to improve standing balance, walking efficiency and running form. If a trainee can’t run currently, I should attempt to return them to function, to be able to run again. I accept that there are always going to be injuries or issues that prevent this journey for some trainees, but the programme should always have that aim or direction of development if it’s going to claim to be functional.

Primates are also the most capable throwers in the animal kingdom and of these, humans are by far the best. Learning to throw effectively gave us an enormous advantage for survival and hunting and has been a big part of our physical development. So, throwing mechanics and movements that improve them should be part of a movement practise.

Other movements that played a big part in our development include Crawling, Climbing, Lifting and Carrying. Babies learn to crawl before they walk and many people argue that skipping this crucial stage (babies that stand up before spending much time crawling) often end up with less functional cores. The same movement experts advocate for us returning to this practise, even in later life, to re-learn the lessons that crawling delivers.

Climbing is also a skill that’s clearly a big part of being a primate. Our ancient primate ancestors were brachiators (they swung through the trees by their arms). Learning how to hang, climb and swing can return function to the upper body because of this evolutionary history.

Biomechanics

Coming at movement from a different perspective, the study of Biomechanics introduces components of movement to consider: motion, force, momentum, levers and balance. Today, I’ll focus mainly on the first component, motion.

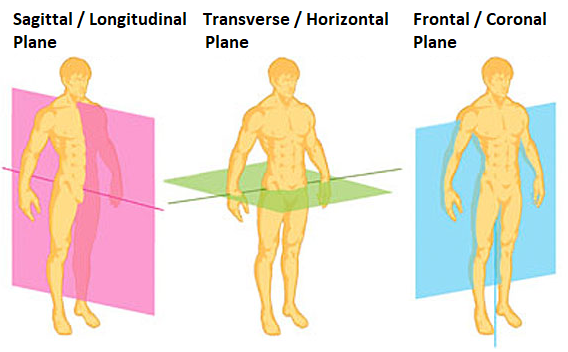

There are 3 principal Planes of Motion in the body:

- Sagittal / Longitudinal – this plane divides the body into left and right.

- Transverse / Horizontal – this plane divides the body into top and bottom.

- Frontal / Coronal – this plane divides the body into front and back.

Most of the movements that you see in more traditional strength and conditioning, at most high street gyms, health clubs, or even gyms which claim to be doing functional fitness, are performed solely on the Sagittal plane (Squats, Deadlifts, Bench, Shoulder Press, Pull Ups, Seated Row etc.). However, the movements described in the previous section, that were crucial to our evolution and to human development, involve movement in the other planes too.

Running, throwing, climbing and crawling all involve heavy elements of both rotational and lateral movement. Watch someone sprint and you’ll see the twisting of the torso and the shift from side to side through the gait cycle. Watch someone throw in any sport, and you won’t see them standing face on to their target, you’ll see them approaching sideways and then whipping the body through a powerful rotation. In fact, most of our movement generates power through using the body like a spring, coiling it and then unleashing the captured, elastic force.

Those same classic gym movements described above are also all Bilateral (both arms/legs move in the same motion simultaneously). Again, if you explore the movements we evolved doing or just watch athletes in their sports today, you’ll find it extremely uncommon for them to move like this. From athletics to ball sports, climbing to dancing, martial arts to swimming, and most activities you can think of, humans rarely move both arms and legs through the same motion at the same time. There are exceptions to this, but the most common thing you’ll see is arms and legs moving unilaterally, in independent directions, and often contralaterally (there is a clear relationship between the arm and the leg on the opposite side).

Anatomical Discoveries

In the 1990s, Tom Myers wrote a book called Anatomy Trains. This book has become like a bible for many physical therapists, personal trainers, massage therapists, athletes, coaches, yoga teachers, chiropractors and osteopaths. In this book, he describes “Myofascial Meridians”, which show the fascial connections between different muscles throughout the body. Fascia is the connective tissue that surrounds all the muscles, organs, bones etc. in the body.

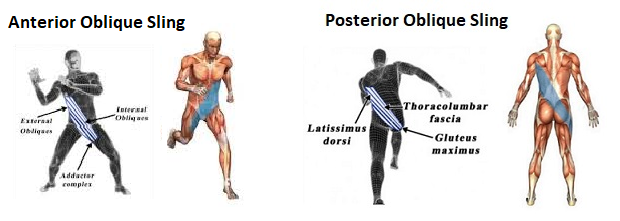

Sometimes also called Anatomy Slings or Myofascial Slings, these fascial connections create lines of action through the body of the force created by muscles. The theory of these Anatomy Slings is that spinal rotation and the muscle systems around the lumbo-pelvic region are at the base of human movement.

The pictures here show the Posterior Oblique Sling and Anterior Oblique Sling. They show the relationship between the opposing hip and shoulder.

The pictures here show the Posterior Oblique Sling and Anterior Oblique Sling. They show the relationship between the opposing hip and shoulder.

This theory overlaps and confirms both the ideas in the Evolutionary Argument and the Biomechanics section and further influences what movements I choose to programme for our trainees.

Conclusion

Whilst I don’t think the bilateral, sagittal plane exercises, which dominate many fitness routines, are redundant, I think the balance of these to other movements can be way less.

If you want to develop absolute strength, picking up the most weight is a part of the equation, and bilateral movements lend themselves well to that. They are also good for creating power output (doing lots of work in as short a time frame as possible), which is why CrossFit utilises them so much. But absolute strength and power output aren’t the be all and end all in training. You can be incredibly strong or a fantastic fitness competitor, but not be very agile or balanced and still be in chronic pain. By prioritising moving well, through optimising your biomechanics, you are more likely to reduce injury risk and pain, move more fluidly and increase your joy of being in your body.

Where many of the programmes I see use 90% or more Bilateral movements, I tend to programme less than 30% in mine. Instead, I use loads of Unilateral (particularly Contralateral), Rotational and Balance based movements.

The interesting thing that I’ve noticed with my trainees is that when they do occasionally do some heavy Deadlifting or Back squatting with a Barbell (Bilateral exercise), they seem to have still made progress by just doing all the Single Leg and Rotational work. I think this is due to the stability and balance they’ve gained, but they’ve managed to achieve this with way less risk and much less vertical loading on their spine.

If you want to see examples of the actual movements that I programme, check out the Fitness for Life YouTube channel or other social media.

Get in touch if you have any questions about this or anything fitness/health related.